Eugen Pentiuc on Christ and the Scriptures

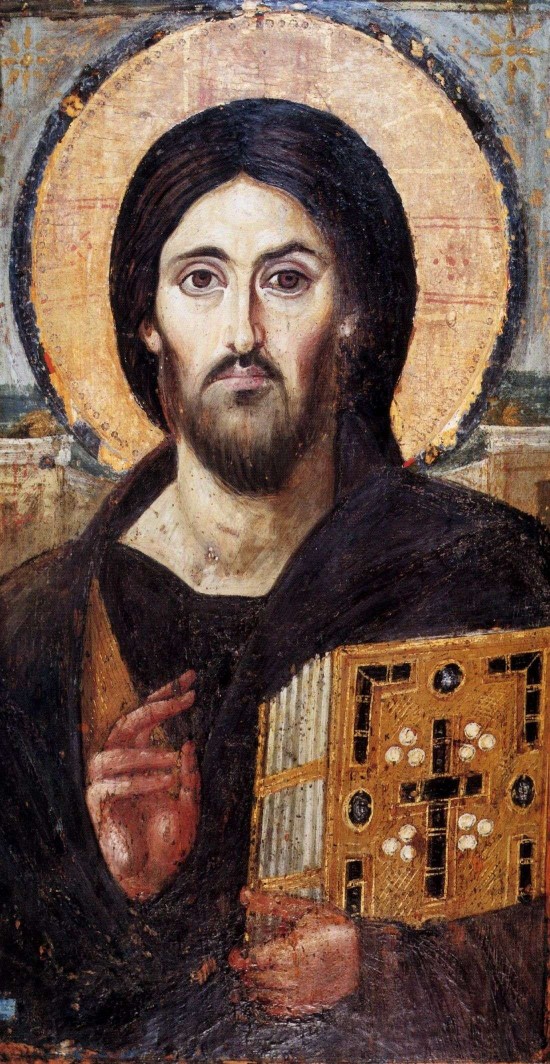

A Blessing Hand and a Cross-Sealed Book… Christianity has always understood itself as a faith and way of life based on one person’s life and sacrifice—that of Christ, and on written records containing the Word of God handed over by prophets and apostles—the books of Old and New Testaments. There is no Scripture without Christ as there is no Christ without Scripture; and this is true for all the historical phases of Christianity. Knowledge of Christ’s person and knowledge of the Scriptures are interdependent elements that make up the very fabric of Christian faith.

A Blessing Hand and a Cross-Sealed Book… Christianity has always understood itself as a faith and way of life based on one person’s life and sacrifice—that of Christ, and on written records containing the Word of God handed over by prophets and apostles—the books of Old and New Testaments. There is no Scripture without Christ as there is no Christ without Scripture; and this is true for all the historical phases of Christianity. Knowledge of Christ’s person and knowledge of the Scriptures are interdependent elements that make up the very fabric of Christian faith.

The raising of the right hand in blessing is a priestly, liturgical gesture, while the other hand is shown gripping tightly the cross-sealed book as if to invite and direct attention toward the precious trove. By this double gesture, the figure with the mysterious two looks suggests that one may approach him in two complementary ways. One may approach him by opening the book and reading its words—never overlooking the cross and the passion signified by it, which is the seal of the entire book, its unifying element. And one may approach him through the hand raised in priestly blessing: through personal dialogue commenced and fostered within the liturgical setting of communal worship. Two ways of discovering Christ: the written word and the liturgical worship.

The same interplay between the written word and live, personal communication is attested further by the Orthodox Divine Liturgy itself, with its two main parts: the “liturgy of the Word” and the “liturgy of the Eucharist.” Like the two hands of the Sinai icon, the two parts of the Divine Liturgy are inseparable. Word and worship are two complementary, intertwining ways toward discovering and rediscovering Christ, and deciphering the enigmatic “code” of his face with its two looks. Worship without word may end up into unwanted magical practices or hollow ritualism. Yet word without worship risks becoming a bookish exercise, with no roots or fruit in reality past or present. It may even turn Christ into a lifeless object of research, disfiguring an irreducible persona into scattered little pieces of an unfinished puzzle.

The scriptural word is able to transform a redundant worship exercise into a unique dialogue, a personal relation that has its starting point in the very self-communication of God. In its turn, worship, especially Eucharistic worship, may vivify the scriptural words, creating a transparent medium between the reader and the reality that lies behind the text: the incarnate Word of God himself.

Eastern Orthodox tradition has always promoted and embodied, since apostolic times, the understanding that Scripture may be interpreted and transmitted not only by the written or uttered word, but also through various channels of communal worship (i.e., aural, visual, ascetic), often labeled generically as Holy Tradition. The Sinai icon directs one’s attention to two channels of testimony regarding Jesus’s person: the book sealed with the cross, and the liturgy in its various expressions of ritual, hymn, and icon.

As Frances M. Young writes, “The earthly life of Jesus was recalled in the context of cultic rites that assumed his divinity. Eventually, though probably beyond our period, the gospel books would be processed with incense in the same kind of way as a pagan idol, and with a similar cultic function, namely, to make the divine present to the worshipper.” Much later, the Seventh Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople in 787 c.e. would confirm this long-standing Christian reverence for the New Testament writings in its teaching that the gospel book was to be venerated equally with the icons, inasmuch as the Gospels constitute together a fourfold verbal icon of Christ. From the outset, Eastern Orthodox tradition has seen in the liturgy a powerful means to link the present, past, and future, and Jesus with his disciples together. The gospel book represents Christ’s person, and is thus censed and venerated with all the pomp and reverence befitting a divine figure. The writing down of the apostles’ “memorials” did not diminish the initial “astonishment” which they themselves experienced: the liturgy helped in keeping this astonishment always fresh and alive 1.

-

Eugen J. Pentiuc The Old Testament in Eastern Orthodox Tradition, Chapter 1 ↩