N. T. Wright on the Kingdom of God

The normal Christian understanding of kingdom, especially of kingdom of heaven, is simply mistaken. “God’s kingdom” and “kingdom of heaven” mean the same thing: the sovereign rule of God (that is, the rule of heaven, of the one who lives in heaven), which according to Jesus was and is breaking in to the present world, to earth. That is what Jesus taught us to pray for. We have no right to omit that clause from the Lord’s Prayer or to suppose that it doesn’t really mean what it says.

The normal Christian understanding of kingdom, especially of kingdom of heaven, is simply mistaken. “God’s kingdom” and “kingdom of heaven” mean the same thing: the sovereign rule of God (that is, the rule of heaven, of the one who lives in heaven), which according to Jesus was and is breaking in to the present world, to earth. That is what Jesus taught us to pray for. We have no right to omit that clause from the Lord’s Prayer or to suppose that it doesn’t really mean what it says.

This is what the resurrection and ascension of Jesus and the gift of the Spirit are all about. They are designed not to take us away from this earth but rather to make us agents of the transformation of this earth, anticipating the day when, as we are promised, “the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea.” When the risen Jesus appears to his followers at the end of Matthew’s gospel, he declares that all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to him. When John the Seer hears the thundering voices in heaven, they are singing, “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he shall reign for ever and ever.” And the point of the gospels—of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John together with Acts—is that this has already begun.

Faced with his beautiful and powerful creation in rebellion, God longed to set it right, to rescue it from continuing corruption and impending chaos and to bring it back into order and fruitfulness. God longed, in other words, to reestablish his wise sovereignty over the whole creation, which would mean a great act of healing and rescue. He did not want to rescue humans from creation any more than he wanted to rescue Israel from the Gentiles. He wanted to rescue Israel in order that Israel might be a light to the Gentiles, and he wanted thereby to rescue humans in order that humans might be his rescuing stewards over creation. That is the inner dynamic of the kingdom of God.

That, in other words, is how the God who made humans to be his stewards over creation and who called Israel to be the light of the world is to become king, in accordance with his original intention in creation, on the one hand, and his original intention in the covenant, on the other. To snatch saved souls away to a disembodied heaven would destroy the whole point. God is to become king of the whole world at last. And he will do this not by declaring that the inner dynamic of creation (that it be ruled by humans) was a mistake, nor by declaring that the inner dynamic of his covenant (that Israel would be the means of saving the nations) was a failure, but rather by fulfilling them both. That is more or less what Paul’s letter to the Romans is all about.

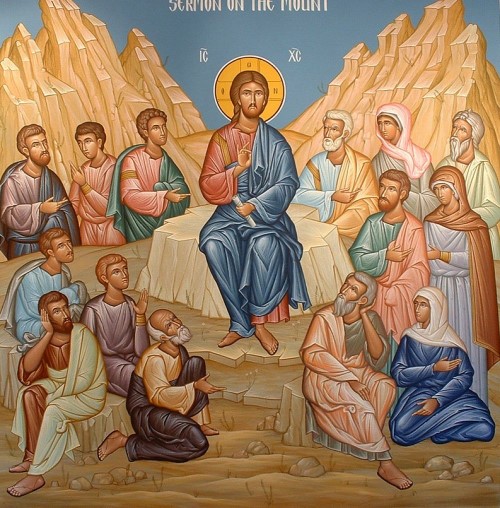

This is the purpose that has been realized in Jesus Christ. One of the greatest problems of the Western church, ever since the Reformation at least, is that it hasn’t really known what the gospels were there for. Imagining that the point of Christianity was to enable people to go to heaven, most Western Christians supposed that the mechanism by which this happened was the one they found in the writings of Paul (I stress, the one they found; I have argued elsewhere that this involved misunderstanding Paul as well) and that the four gospels were simply there to give backup information about Jesus, his teaching, his moral example, and his atoning death. This long tradition screened out the possibility that when Jesus spoke of God’s kingdom, he was talking not about a heaven for which he was preparing his followers but about something that was happening in and on this earth, through his work, then through his death and resurrection, and then through the Spirit-led work to which they would be called 1.

-

N. T. Wright Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church Part III, Chapter 12 ↩